Antonio Banderas turns 65: "I think I'm one of those people who will die if they stop."

Antonio Banderas 's (65-year-old Malaga) office in the Soho theater isn't particularly striking. It's medium-sized, without ostentation. It seats three people at most. There are some souvenirs, though. Larger is an adjoining meeting room, from where you can see the rest of the staff (all women that day, with whom he'll have lunch at the end of the morning) thanks to the glass walls that enclose the offices. To the right of Banderas, sitting behind the computer, the window overlooks a narrow street, and pedestrians can be glimpsed through the sloping slats of the shutters. Any passerby could look up and see the Malaga native. In reality, Banderas doesn't hide from his audience. He never has. Even less so in his current life in his hometown. He lives across from the Roman theater and the Alcazaba, in the center. "Today I ran eight kilometers around the port," he notes.

The day before, Banderas had lunch with Robert De Niro in Marbella. “He told me that, regardless of whether you like Megalopolis or not, he greatly respected the fact that Coppola had paid for the entire film [$120 million, €103 million]. He sold part of his vineyards to produce it; he didn't put anyone into debt. It's his money,” he explains. Unconsciously or not, the Malaga native has just drawn a parallel with what he's doing in the Andalusian city: he's invested in restaurants and other businesses that have fared better or worse, but his heart and his money are in his crown jewel, this Soho theater that's hosting the talk.

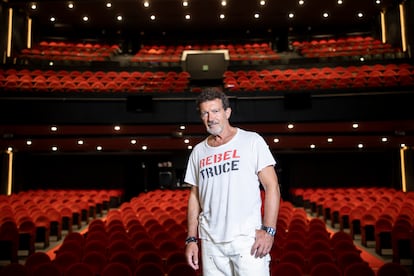

During the walk through the venue beforehand, every time Banderas accelerated his speech—he appears polite to the journalist, though with the emotional handbrake on; he's not the usual explosive Antonio, and the reason is explained later—it was because he was pointing out details of the venue designed to enhance the audience's experience, such as the transparent railings in the amphitheater that don't obstruct the view and can even be lowered to hide them during performances. All for the audience's enjoyment. There's also the Sohrlin production and teaching space, a project he's been working on for many years. "We have to teach, we have to support creation, so there are places to rehearse." However, his favorite is the theater, where he even has a reserved dressing room: number 5.

This Sunday, August 10th, Banderas turns 65. The talk took place on July 21st, one of the few days the actor visited Málaga. In chronological order: at the beginning of the summer, he was in Boston, filming Tony, a biopic of the famous chef Anthony Bourdain, focusing on his early days. In this film, the Malaga native played a chef who adopts a lost and rebellious teenage Bourdain into his kitchen ("You never know with movies, but this one is complicated, emotionally complex, with things that are very difficult to write and describe, and it still turns out to be a great film").

He then traveled to the Canary Islands to work on the thriller Above and Below, and on July 28th, filming began in London on Rose's Baby, the second feature-length feature film directed by Trudie Styler, a documentary filmmaker known in the film world for her keen eye as a producer and in the music world for being Sting's wife. "It's a tremendous script. I'm the ex-husband of a divorced couple, the kind who can't stand each other, and who are united by one thing: their love for their teenage daughter," explains Banderas, who weighs his words and the names he mentions so as not to betray confidentiality clauses. "And suddenly they have to reunite because, for their daughter to overcome her illness, the doctors only offer one solution: for them to have another child."

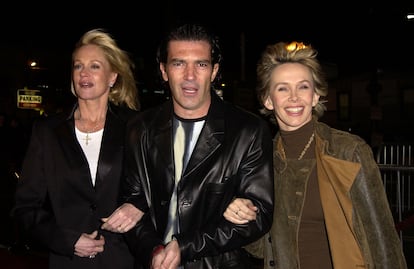

The actor raves about the tone of the script, the cast, the insights emanating from a story that delves into the concept of family, and how this Rose's Baby exemplifies his vital network of contacts. “Melanie [Griffith, his second ex-wife] became good friends with Sting and Trudie on the set of Thunder Monday. Over the years, when they went to Los Angeles, they would stop by our house. And we talked a lot about life, especially with Trudie. Of course, having read the script and in hindsight, thanks to years and years of mutual conversations, she offered me the project because she's seen me in those situations, she has a lot of vital information about me. And she won't let me lie, she won't allow me to lie like that, which one tries to pass off as truth in acting, which is countered when the director says to you: 'Do you think you're telling the truth?' In the end, everything is the truth. Whether you're making an impressionist or expressionist film, there are truths. Even the changes in tone don't matter, whether you go from Pain and Glory to Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny: "Every job contains its truth."

Hence the energy saving: in the mornings that week in July, he goes to meetings and events at the theater, and the afternoons he spends locked away in his house, alone, studying the script. “I learned from an interview with Peter O'Toole that scripts aren't learned, they're studied. It's very different.” For that, he needs to gather his strength and his emotions. “Nicole [Kimpel, his partner since 2014] has stayed in Marbella.” And what will he do on his birthday? “I'll spend it on set; I suppose there'll be some surprise celebration there, and then I'll have dinner with Nicole and my dog.” What the actor didn't calculate at the end of July is that August 10th would fall on a Sunday. So he won't be filming, and more family may join him for the celebration in London. “All in all, the films I've shot on my birthday have always brought me luck.” An example? “Pain and Glory.”

The eight-kilometer morning run turns the conversation to the heart attack he suffered in 2017. “It was one of the best things that's ever happened to me. Seriously. There are many types of heart attacks, each person experiences them differently; in fact, 30% of those who suffer one don't even realize it. Mine was a truly serious warning. It changed my understanding of life,” he recalls. “For example, the night before I smoked my last cigarette. Beyond my health, it made me question why I was an actor, what I wanted to do with the rest of my life. And the subsequent reflection brought me back to the stage.”

When he won the award for Best Actor at the Cannes Film Festival, this journalist encountered Banderas crying with the award in his hand. Isn't the Oscar more important than the Cannes trophy? His response that May 2019 was: "I'm a theater actor, this is the greatest." Six years later, he underscores that conviction: "Due to the triumph of digital technology and artificial intelligence, we don't know what's true and what's false. That line has become extraordinarily blurred. And theater has become a kind of refuge for truth. There are many truths that can visit a stage, depending on who writes a play, who directs it, the actors... Although there is one reality, one that is objective to everyone, and that is that there is a group of people, made of flesh and blood, telling a story to another group of people, made of flesh and blood. Of course, technology has always been closely linked to theater. The Greeks used sound effects. But it has never replaced human beings. The creation of characters happens in real time."

And why his passion for musicals? “Because my first connection with acting was through musical theater. In fact, in 1975 I saw Godspell in Málaga with an impressive actor, Nicolás Romero. And four months after Franco's death, Hair came to the Cervantes [the Málaga theater]. I had never seen anything like it before, and it caused me enormous anxiety. I'm a huge music lover; I listen to music every day, and it was music that led me to the theater.” Banderas recounts, with color and passion in his narration, those years of apprenticeship, with curious characters who settled in his city, like Edgar Neville's widow, and his step-by-step transformation from José Antonio Domínguez Bandera into Antonio Banderas. “The first play I did as a professional was Los Tarantos, directed by Luis Balaguer, who was an assistant director for Tamayo, in Almagro, although it wasn't part of his competition. You see? Music and theater.” The actor shows off his memory, starting with lists of colleagues and dates, illuminating the path that made him Banderas.

From that office near Málaga's Alameda, Hollywood seems distant. "Well, not so much, because Hollywood isn't a physical place anymore. When I moved there, you had to go to parties, appear in certain places, and be seen. Today, Hollywood is a brand and a label applied to those of us who work in that industry, a characteristic that remains in the public's subconscious. And it's not bad for me when they call me for industrial films, because that way I can pay for this [opens arms]. On the musical Gypsy, I had 26 musicians, 35 actors, and about 40 technicians of all kinds. That cost 180,000 euros a week. Well, I also told you that I watched it 88 times to take notes and, for example, cut 17 minutes from the first act."

Banderas, the businessman and theater director, has relegated, almost assassinated, Banderas, the filmmaker. "This project is very serious, with zero public funding, mind you, it needs a lot of attention. Now, for example, we're going to open it up to dance, although..." And he launches into an idea he's developing, for when he secures the rights, of a Sweeney Todd that would combine musical and audiovisual work: in his head, it's already complete. "It's also that directing films requires an effort..." and he laughs flirtatiously.

“When I was 20, I thought 65-year-olds used to walk with a cane,” he confesses, laughing. “I don't feel that way; I don't see the end coming... Maybe I'm doing things I shouldn't be doing. But the doctors don't tell me anything. They say I'm fine, I can do what I want, exercise, read... Before, at 65, you retired. Now, no, it's later.” And he doesn't see himself, nor does he ever see himself, retired. “Look, now I'm going to start music theory classes, and I've bought a piano. I think it's one of those pianos where if you stop, you'll die. And I work doing what I love; it's been the luck of my life.”

He confesses to being scared, very concerned about "current world politics." He recalls the day Pedro Almodóvar and Cecilia Roth crossed paths with him while he was performing in the theater and convinced him to make films and change his name to the current Antonio Banderas. He faces the ultimate question: does anyone contradict him today? "All of them [he points to the theater staff, laughing]. Every time I throw out a crazy idea, they respond with a no. And in life, of course, my brother Javier. And Nicole, but she doesn't confront me, but rather redirects me in a very subtle way, until I get to the other side. Yes, luckily there are people who argue with me."

EL PAÍS

%3Aformat(jpg)%3Aquality(99)%3Awatermark(f.elconfidencial.com%2Ffile%2Fbae%2Feea%2Ffde%2Fbaeeeafde1b3229287b0c008f7602058.png%2C0%2C275%2C1)%2Ff.elconfidencial.com%2Foriginal%2F5d1%2F9a1%2F007%2F5d19a1007aa2dc7fc503fabd38bba65e.jpg&w=3840&q=100)

%3Aformat(jpg)%3Aquality(99)%3Awatermark(f.elconfidencial.com%2Ffile%2Fbae%2Feea%2Ffde%2Fbaeeeafde1b3229287b0c008f7602058.png%2C0%2C275%2C1)%2Ff.elconfidencial.com%2Foriginal%2Fcf4%2F399%2F9b1%2Fcf43999b1150521c66b126806b23fab1.jpg&w=3840&q=100)